ASD is pleased to share this guest blog post from Funeral Director and Author, Todd Harra of McCrery and Harra Funeral Home in Wilmington, DE. Todd’s new book, Last Rites: The Evolution of the American Funeral will be published next month on August 2nd and is now available for preorder here. This is a perfect coffee table book to add to your collection that explains why we bury our dead the way we do in a non-textbook type manner. To read a sneak peak of the book, click here.

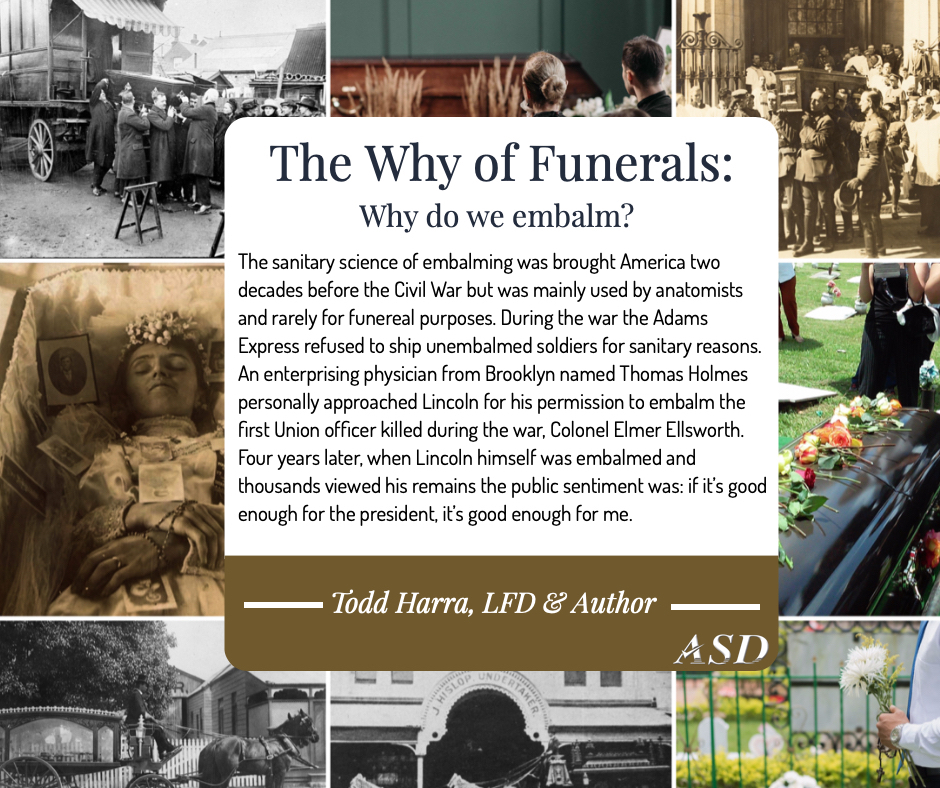

Why do we embalm?

The sanitary science of embalming was brought America two decades before the Civil War but was mainly used by anatomists and rarely for funereal purposes. During the war the Adams Express refused to ship unembalmed soldiers for sanitary reasons. An enterprising physician from Brooklyn named Thomas Holmes personally approached Lincoln for his permission to embalm the first Union officer killed during the war, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth. Four years later, when Lincoln himself was embalmed and thousands viewed his remains the public sentiment was: if it’s good enough for the president, it’s good enough for me.

Why a casket and not a coffin (or shroud)?

Simple answer is: resources. Shrouded (“chested” burial was reserved for royalty and gentry) burials were the norm in England due to limited resources and a mature population. In America, the Puritans discovered a seemingly unlimited supply of wood, and everyone (even enslaved peoples) were afforded encoffined burial. In 1858 Crane, Breed, & Co. introduced their metallic burial “casket,” a less anthropomorphic shaped-vessel than the coffin that appealed to the Victorian era’s sense of softening death.

How did funeral flowers become a thing?

Funeral historian Bertram Puckle offers the pat explanation, “[it saves] the mental exercise of composing a suitable letter of condolence.” Puckle is only partly joking. The impulse to send flowers is one that dates back to at least35,000 years (based on archaeologist Ralph Solecki’s find in an Iraqi cave) and stems from the emotional impulse to surround the ugliness of death with beauty. Flowers also had the added benefit of masking unpleasant odors prior to the advent of embalming.

What’s up with mourning jewelry?

Mourning jewelry originates from the medieval custom of distributing mourning clothes, or dooles—the idea being that every time one wore their gloves or scarf they would think of the deceased. In America, this tradition morphed from not just clothingbut to expensive luxury items like books, rings, brooches, and wine. Funeral costs got so out of controlthat many states enacted sumptuary laws banning funeral gifts though displays of mourning (in the form of jewelry) made a revival during WWI. In contemporary times mourning jewelry often takes the form of cremation jewelry.

Funeral directors—where’d they come from?

Prior to the Civil War the predecessor of the funeral director were called tradesman undertakers, men (always men in those times) who undertook the duties of burying the town’s dead because of their vocation. Carpenters, cabinet makers, joiners, chandlers, and upholders were trades commonly associated with undertaking because of what they made (e.g., furniture—including coffins, candles, upholstery [for coffins], etc.). After the war, these tradesman undertakers began to practice embalming, shed their original vocations, and specialized in undertaking. Undertakers organized in the form of associations to set standards, and the term “funeral director” was officially adopted in 1882 at the first meeting of the National Funeral Directors Association.

What’s the Story with the Funeral Luncheon?

The post funeral meal has been around as long as civilization has existed as a way for mourners to commune in grief. The Egyptians shared a meal at the tomb following burial, and the Romans built elaborate kitchens in their mausolea complete with a libation pipe to connecting the living and the dead where food and drink could be shared. In medieval Europe the funeral feast was called the “averil” which literally means heir ale—or meal welcoming the heir to the title/inheritance. Colonial funeral meals were elaborate booze-soaked affairs that could (and often did) comprise 95 percent of the total funeral bill.

For more information read Todd’s new book Last Rites: The Evolution of the American Funeral.

About the Author

Todd Harra is a licensed funeral director, embalmer, certified postmortem deconstructionist, cremationist, and one of the foremost experts on the history (and future) of burial rites in the United States. Todd has written two nonfiction books about the profession and is an associate editor for Southern Calls, a renowned journal in the funeral profession. He is the president of the Delaware State Funeral Directors Association.

Related Reading

18 Questions With Funeral Director and Amazon Bestselling Author, Todd Harra

10 Fascinating Chapters in Funeral History You Didn’t Learn in Mortuary School

Overachieving Undertakers – How Funeral Director Inventors Changed History

About The Author

Jess Farren (Fowler)

Jess Farren (Fowler) is a Public Relations Specialist and Staff Writer who has been a part of the ASD team since 2003. Jess manages ASD’s company blog and has been published in several funeral trade magazines. She has written articles on a variety of subjects including communication, business planning, technology, marketing and funeral trends. You can contact Jess directly at Jess@myASD.com